We have seen this example

A (7)

/ | \

B(5) C(6) D(1)

…

“These numbers in brackets are heuristic values (h).

Smaller h means the node looks closer to the goal.”

So we understood that h guides the search —

but u might now wonder, “Where do these numbers come from?”

what heuristic actually means

“A heuristic is like an educated guess that helps the computer decide

which direction looks best to reach the goal.

These h-values aren’t magic — we calculate them using some kind of formula or logic

that depends on the problem we are solving.”

heuristic values can be computed

there are different ways to calculate heuristic values,

depending on the type of problem.

2 categories:

🅰️ 1. Geographical or Coordinate-based Problems

Example: Path finding between cities, robot moving on a grid, GPS maps.

Here we can use distance formulas like:

🔹 Euclidean Distance

If you have two points:

- P₁(x₁, y₁)

- P₂(x₂, y₂)

Then the Euclidean distance (used as heuristic h) is:

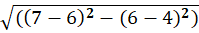

h(P1,P2)=

It gives the straight-line distance between the node and the goal.

🔹 Manhattan Distance

h(n)=∣x2−x1∣+∣y2−y1∣

Used in grid-based problems (like robot moving up, down, left, right).

Example:

If you are moving from (2,3) to goal (5,7):

- Euclidean = √[(5−2)² + (7−3)²] = √(9 + 16) = 5

- Manhattan = |5−2| + |7−3| = 3 + 4 = 7

When We Use Euclidean Distance (or similar distance)

We use a distance-based heuristic in Best-First Search whenever:

- The problem has nodes with geographical positions, like coordinates (x, y)

- You’re solving a pathfinding or map navigation problem

- The nodes represent locations (cities, intersections, grid points)

In such cases, Euclidean distance (or straight-line distance) is a perfect heuristic estimate

because it gives a direct measure of “how far the goal looks”.

Example: Route Finding Problem

Suppose we are trying to go from City A to City G.

A ——— B ——— C

| ↘

| G

D ——— E ——— F

Each city has coordinates:

| City | Coordinates (x, y) |

| A | (2, 3) |

| G (Goal) | (7, 6) |

| B | (4, 3) |

| C | (6, 4) |

| E | (3, 5) |

Now, from each city, we can calculate:

h(n)=

This tells how “close” that city appears to the goal.

Example Calculation

From A (2,3) to G (7,6):

h(A)= =

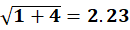

From C (6,4) to G (7,6):

h(C)=

=

So, Best-First Search will expand C before A,

because h(C) < h(A) — meaning C looks closer to the goal.

Example: Route Finding Using Euclidean Distance (Best-First Search)

Goal of the Example

It is showing that heuristic values (h) —

like the ones we used in tree example —

can be calculated using Euclidean distance when the problem involves locations or coordinates.

We can see how numbers like h(A)=5.83, h(C)=2.23 actually come from a formula, not just “given”.

Problem Setup

We can see using other example

(2,3) (4,3) (6,4) (7,6)

A ——– B ——– C ——– D (Goal)

“Imagine we have four cities — A, B, C, and D.

City D is our goal, located at coordinate (7,6).

The other cities are spread out on a map, each with its own (x, y) coordinate.

Our task is to go from A → D,

and we’ll use Best-First Search with a heuristic based on Euclidean distance —

which means straight-line distance to the goal.”

Heuristic Formula (on the board)

h(n)=

where

- (x₁, y₁) = coordinates of current node

- (x₂, y₂) = coordinates of goal node

Step-by-Step Calculation

| City | Coordinates | Goal (7,6) | Calculation | h(n) |

| A | (2,3) | (7,6) | √[(7−2)² + (6−3)²] = √(25 + 9) | 5.83 |

| B | (4,3) | (7,6) | √[(7−4)² + (6−3)²] = √(9 + 9) | 4.24 |

| C | (6,4) | (7,6) | √[(7−6)² + (6−4)²] = √(1 + 4) | 2.23 |

| D | (7,6) | (7,6) | √[(0)² + (0)²] = 0 | 0 |

“The heuristic value (h) tells us how close each city is to the goal,

in terms of straight-line distance.

The smaller the h-value, the closer that city appears to the goal.”

So, in order of closeness:

D (0) < C (2.23) < B (4.24) < A (5.83)

Step-by-Step Best-First Search Behavior

Now, apply the Best-First Search rule:

“Always pick the city with the smallest h-value next.”

| Step | City Visited | Heuristic h(n) | Next Chosen City |

| 1 | Start at A (5.83) | — | Next → B (4.24) |

| 2 | From B (4.24) | — | Next → C (2.23) |

| 3 | From C (2.23) | — | Next → D (0) |

| 4 | Reached Goal D (0) | — | Stop |

Path found: A → B → C → D

We start at city A, which is farthest from the goal (h=5.83).

From there, we look at which city appears closer to the goal, using the straight-line distance.

City B (h=4.24) looks closer than A,

then C (h=2.23) looks even closer,

and finally, D is the goal (h=0).

So our Best-First Search will follow the path A → B → C → D,

because at each step, it picks the city with the smallest heuristic value.”

🅱️ 2. Puzzle or Logical Problems

Example: 8-puzzle problem or similar AI puzzles.

Here, we can’t measure physical distance,

so we use problem-based heuristics, such as:

🔹 Number of Misplaced Tiles

Count how many tiles are not in the right place.

🔹 Sum of Manhattan Distances for all tiles

Add up how far each tile is from where it should be.

🔹 Number of Wrong Positions or Out-of-Order Elements

Each of these gives us a heuristic estimate of “how far” we are from the solution —

but using logical distance, not physical distance.

Examples of heuristic functions:

| Problem Type | Heuristic Example |

| Route / Map | Euclidean distance |

| Grid / Maze | Manhattan distance |

| 8-puzzle | Number of misplaced tiles |

| Word transformation | Number of wrong letters |

| Game (chess) | Number of possible moves or material difference |

“In some problems, we can actually measure distance using coordinates —

so we use formulas like Euclidean distance as our heuristic.

But in other problems — like the 8-puzzle or chess —

there’s no concept of distance on a map,

so we design different kinds of heuristic functions

that estimate how far we are from the goal based on the problem’s rules.”

The heuristic is not fixed — it depends on the nature of the problem.

That’s why in our tree example, we were given heuristic values —

but in real AI systems, those h-values are calculated

using distance formulas, problem logic, or experience (learned heuristics).

In our tree problem, heuristic values were already given.

But in real-life problems, those values can come from many sources —

sometimes by measuring distance (like Euclidean),

sometimes by counting differences (like misplaced tiles),

or sometimes by estimating future cost.

That’s why heuristic design is the most creative part of AI search!

Properties of Best-First Search

1. Completeness

❌ Not complete.

It might get stuck exploring paths that look good (low h),

but actually lead to dead ends.

2. Optimality

Not optimal.

It doesn’t always find the shortest or least-cost path —

it only follows the path that looks best using h(n).

3. Time and Space Complexity

If:

- b = branching factor (average number of children per node)

- m = maximum depth of the search tree

Then:

Time Complexity= O(bm)

Space Complexity= O(bm)

(Because it keeps all generated nodes in memory.)

4. Evaluation Function

For Best-First Search:

f(n)= h(n)

That means it depends only on the heuristic,

not on the path cost.

In Best-First Search, the algorithm behaves like a person trying to reach a destination by always choosing the road that looks shortest or closest — based on a guess.

Sometimes, this guess works well; sometimes, it leads to a dead end.

So it’s fast but not guaranteed to be correct.

Advantages

- Uses heuristic → more intelligent than uninformed searches like BFS or DFS.

- Faster in many cases.

- Requires less exploration in simple problems.

Disadvantages

- May get stuck in loops or local minima.

- Not always complete.

- Not guaranteed to find the optimal path.

- Depends heavily on how good the heuristic is.